When Did France Become a Republic Again

| France République française | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1848–1852 | |||||||||

| Flag Great Seal | |||||||||

| Motto: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" | |||||||||

| Anthem:Le Chant des Girondins "The Song of Girondists" | |||||||||

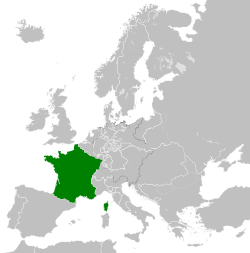

The French Democracy in 1848 | |||||||||

| Uppercase | Paris | ||||||||

| Common languages | French | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (majority religion) Calvinism Lutheranism Judaism | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential commonwealth (1848–1851) Unitary disciplinarian presidential republic (1851–1852) | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

| • 1848–1852 | Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

| • 1849–1852 | Henri Georges Boulay de la Meurthe | ||||||||

| Prime number Minister | |||||||||

| • 1848 (first) | Jacques-Charles Dupont | ||||||||

| • 1851 (last) | Léon Faucher | ||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| • French Revolution | 23 February 1848 | ||||||||

| • Abolition of slavery | 27 Apr 1848 | ||||||||

| • Constitution adopted | 4 Nov 1848 | ||||||||

| • Coup d'état | 2 December 1851 | ||||||||

| • Establishment of the Second Empire | 2 December 1852 | ||||||||

| Currency | French Franc | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | FR | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | France Algeria | ||||||||

The French Second Republic (French: Deuxième République Française or La IIe République ), officially the French Republic (République française), was the republican regime of France that existed between 1848 and 1852. It was established in Feb 1848, with the February Revolution that overthrew the July Monarchy, and ended in Dec 1852, after the 1851 coup d'état and when president Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte proclaimed himself Emperor Napoleon III and initiated the 2nd French Empire. It officially adopted the motto of the First Democracy, Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.

Revolution of 1848 [edit]

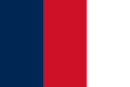

Variant of the French tricolor flag used past the Republic for a few days, between 24 February and five March 1848[1]

The 1848 Revolution in France, sometimes known every bit the February Revolution, was one of a wave of revolutions across Europe in that year. The events swept away the Orleans monarchy (1830–1848) and led to the creation of the nation'due south 2nd republic.

The Revolution of 1830, part of a moving ridge of similar regime changes across Europe, had put an end to the monarchy of the Bourbon Restoration and installed a more liberal ramble monarchy under the Orleans dynasty and governed predominantly past Guizot's bourgeois-liberal centre-right and Thiers'southward progressive-liberal center-left.

Merely to the left of the dynastic parties, the monarchy was criticised past Republicans (a mixture of Radicals and socialists) for being insufficiently autonomous: its balloter system was based on a narrow, privileged electorate of holding-owners and therefore excluded workers. During the 1840s several petitions requesting balloter reform (universal manhood suffrage) had been issued past the National Guard, but had been rejected by both of the master dynastic parties. Political meetings defended to this issue were banned by the government, and electoral reformers therefore bypassed the ban past holding a serial of 'banquets' (1847–1848), events where political debate was disguised every bit dinner speeches. This movement began overseen by Odilon Barrot's moderate center-left liberal critics of Guizot's bourgeois government, merely took on a life of its own later 1846, when economic crisis encouraged ordinary workers to demand a say over government.

On 14 February 1848 Guizot'south regime decided to put an terminate to the banquets, on the grounds of constituting illegal political assembly. On 22 February, striking workers and republican students took to the streets, enervating an end to Guizot's government, and erected barricades. Odilon Barrot called a movement of no confidence in Guizot, hoping that this might satisfy the rioters, only the Sleeping accommodation of Deputies sided with the premier. The government called a country of emergency, thinking it could rely on the troops of the National Guard, merely instead on the morning of 23 February the Guardsmen sided with the revolutionaries, protecting them from the regular soldiers who by now had been called in.

The industrial population of the faubourgs was welcomed by the National Guard on their mode towards the centre of Paris. Barricades were raised later the shooting of protestors outside the Guizot estate by soldiers.

On 23 Feb 1848 premier François Guizot'southward cabinet resigned, abased by the petite bourgeoisie, on whose support they thought they could depend. The heads of the more left-leaning bourgeois-liberal monarchist parties, Louis-Mathieu Molé and Adolphe Thiers, declined to form a government. Odilon Barrot accustomed, and Thomas Robert Bugeaud, commander-in-main of the first armed services partition, who had begun to attack the barricades, was recalled. In the face of the insurrection that had now taken possession of the whole capital letter, Male monarch Louis-Philippe abdicated in favour of his 9-year-quondam grandson, Prince Philippe, Count of Paris, but under force per unit area of insurgents who invaded the chamber of the Chamber of Deputies, leaders leaned in favor of the coup and prepared a provisional government; a (2nd) republic was then proclaimed past Alphonse de Lamartine.

This provisional government, with Dupont de l'Eure every bit its president, consisted of Lamartine for foreign affairs, Crémieux for justice, Ledru-Rollin for the interior, Carnot for public instruction, Goudchaux for finance, Arago for the navy, and Burdeau for state of war. Garnier-Pagès was mayor of Paris.

Only, every bit in 1830, the republican-socialist party prepare a rival government at the Hôtel de Ville (metropolis hall), including Louis Blanc, Armand Marrast, Ferdinand Flocon, and Alexandre Martin, known as Albert 50'Ouvrier ("Albert the Worker"), which bid off-white to involve discord and ceremonious war. But this time the Palais Bourbon was not victorious over the Hôtel de Ville. It had to consent to a fusion of the ii bodies, in which, however, the predominating elements were the moderate republicans. It was uncertain what the policy of the new government would be.

One party seeing that in spite of the changes in the last lx years of all political institutions the position of the people had non been improved, demanded a reform of society itself, the abolitionism of the privileged position of property, which they viewed every bit the only obstacle to equality, and as an emblem hoisted the red flag (the 1791 cerise flag was, withal, the symbol not merely of the French Revolution, only rather of martial police force and of order[two]). The other party wished to maintain society on the basis of its traditional institutions, and rallied round the tricolore. As a concession made by Lamartine to popular aspirations, and in substitution of the maintaining of the tricolor flag, he conceded the Republican triptych of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, written on the flag, on which a red rosette was also to exist added.[two]

The first standoff took place as to the form which the 1848 Revolution was to take. Lamartine wished for them to maintain their original principles, with the whole state every bit supreme, whereas the revolutionaries under Ledru-Rollin wished for the democracy of Paris to hold a monopoly on political power. On v March the government, nether the pressure of the Parisian clubs, decided in favour of an immediate reference to the people, and direct universal suffrage, and adjourned information technology until 26 April. This added the uneducated masses to the electorate and led to the election of the Elective Assembly of 4 May 1848. The provisional regime having resigned, the republican and anti-socialist majority on 9 May entrusted the supreme power to an Executive Committee consisting of five members: Arago, Pierre Marie de Saint-Georges, Garnier-Pagès, Lamartine and Ledru-Rollin.

The result of the general election, the return of a elective associates, predominantly moderate, if not monarchical, dashed the hopes of those who had looked for the establishment, by a peaceful revolution, of their ideal socialist country; but they were not prepared to yield without a struggle, and in Paris itself they commanded a formidable force. In spite of the preponderance of the "tri-colour" party in the provisional government, so long as the phonation of France had not spoken, the socialists, supported past the Parisian proletariat, had exercised an influence on policy disproportionate to their relative numbers. By the decree of 24 February, the conditional government had solemnly accepted the principle of the "right to work," and decided to constitute "National Workshops" for the unemployed; at the same time, a sort of industrial parliament was established at the Luxembourg Palace, nether the presidency of Louis Blanc, with the object of preparing a scheme for the system of labor; and, lastly, past the prescript of 8 March, the property qualification for enrollment in the National Guard had been abolished and the workmen were supplied with arms. The socialists thus formed a sort of land-within-a-state, complete with a government and an armed force.

1848 uprisings [edit]

On 15 May, an armed mob, headed by Raspail, Blanqui and Barbès, and assisted past the proletariat-aligned Guard, attempted to overwhelm the Associates, but were defeated by the bourgeois-aligned battalions of the National Guard. Meanwhile, the national workshops were unable to provide remunerative work for the genuine unemployed, and of the thousands who applied, the greater number were employed in aimless digging and refilling of trenches; shortly even this expedient failed, and those for whom work could non be invented were given a one-half wage of 1 franc a twenty-four hour period.

On 21 June, Alfred de Falloux decided in the proper name of the parliamentary commission on labour that the workmen should be discharged within three days and those who were able-bodied should be forced to enlist in the armed forces.

After this, the June Days Uprising bankrupt out, over the grade of 24–26 June, when the eastern industrial quarter of Paris, led by Pujol, fought the western quarter, led past Louis-Eugène Cavaignac, who had been appointed dictator. The socialist political party was defeated and afterwards its members were deported. But the democracy had been discredited and had already go unpopular with both the peasants, who were exasperated past the new land tax of 45 centimes imposed in club to fill the empty treasury, and with the suburbia, who were intimidated by the ability of the revolutionary clubs and disadvantaged by the economic stagnation. By the "massacres" of the June Days, the working classes were also alienated from information technology. The Duke of Wellington wrote at this time, "France needs a Napoleon! I cannot yet see him..." The granting of universal suffrage to a club with Imperialist sympathies would benefit reactionaries, which culminated in the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as president of the republic.

Constitution [edit]

The new constitution, proclaiming a democratic republic, direct universal suffrage and the separation of powers, was promulgated on 4 November 1848.[three] Under the new constitution, there was to be a single permanent Assembly of 750 members elected for a term of iii years by the scrutin de liste. The Associates would elect members of a Council of State to serve for 6 years. Laws would be proposed by the Council of State, to be voted on by the Associates. The executive power was delegated to the President, who was elected for iv years by direct universal suffrage, i.e. on a broader basis than that of the Assembly, and was not eligible for re-election. He was to cull his ministers, who, similar him, would be responsible to the Associates. Finally, revision of the constitution was made practically impossible: it involved obtaining three times in succession a majority of three-quarters of the deputies in a special associates. It was in vain that Jules Grévy, in the name of those who perceived the obvious and inevitable adventure of creating, nether the name of a president, a monarch and more a king, proposed that the head of the state should be no more than a removable president of the ministerial council. Lamartine, thinking that he was sure to be the pick of the electors under universal suffrage, won over the back up of the Bedchamber, which did not even take the precaution of rendering ineligible the members of families which had reigned over France. It made the presidency an role dependent upon pop acclamation.

Presidential election of 1848 [edit]

The election was keenly contested; the autonomous republicans adopted as their candidate Ledru-Rollin, the "pure republicans" Cavaignac, and the recently reorganized Imperialist party Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. Unknown in 1835, and forgotten or despised since 1840, Louis Napoleon had in the concluding eight years advanced sufficiently in the public interpretation to be elected to the Constituent Assembly in 1848 by five departments. He owed this rapid increment of popularity partly to blunders of the government of July, which had unwisely aroused the memory of the land, filled every bit information technology was with recollections of the Empire, and partly to Louis Napoléon'due south campaign carried on from his prison at Ham by means of pamphlets of socialistic tendencies. Moreover, the monarchists, led by Thiers and the commission of the Rue de Poitiers, were no longer content even with the safe dictatorship of the upright Cavaignac, and joined forces with the Bonapartists. On 10 December the peasants gave over 5,000,000 votes to a name: Napoléon, which stood for society at all costs, confronting 1,400,000 for Cavaignac.

Henri Georges Boulay de la Meurthe was elected Vice President, a unique position in French history.

Presidency of Louis Napoléon [edit]

For three years, there was an indecisive struggle between the heterogeneous Assembly and the President, who was silently awaiting his opportunity. He chose as his ministers men with piffling inclination towards republicanism, with a preference for Orléanists, the master of whom was Odilon Barrot. In lodge to strengthen his position, he endeavored to conciliate the reactionary parties, without committing himself to whatsoever of them. The principal example of this was the trek to Rome voted past the Catholics, to restore the temporal authority of the Pope Pius Ix, who had fled Rome in fear of the nationalists and republicans. (Garibaldi and Mazzini had been elected to a Constitutional Assembly.) The Pope called for international intervention to restore him in his temporal power. The French President moved to establish the power and prestige of French republic confronting that of Austria, as starting time the piece of work of European renovation and reconstruction which he already looked upon every bit his mission. French troops under Oudinot marched into Rome. This provoked a foolish insurrection in Paris in favor of the Roman Republic, that of the Château d'Eau, which was crushed on thirteen June 1849. On the other hand, when the Pope, though only but restored, began to yield to the full general movement of reaction, the President demanded that he should set up a Liberal authorities. The Pope's dilatory answer having been accepted by the French ministry, the President replaced it on 1 November, by the Fould-Rouher cabinet.[iv]

This looked like a declaration of war confronting the Catholic and monarchist majority in the Legislative Assembly, which had been elected on 28 May in a moment of panic. Just the President once more pretended to exist playing the game of the Orléanists, as he had done in the case of the Constituent Associates. The complementary elections of March and April 1850 resulted in an unexpected victory for the republicans which alarmed the conservative leaders, Thiers, Berryer and Montalembert. The President and the Assembly co-operated in the passage of the Loi Falloux of 15 March 1850, which again placed university pedagogy under the management of the Church.[5]

A conservative electoral law was passed on 31 May. It required each voter to bear witness three years' residence at his current address, by entries in the record of directly taxes. This effectively repealed universal suffrage: factory workers, who moved adequately often, were thus disenfranchised. The law of sixteen July aggravated the severity of the press restrictions past re-establishing the "caution money" (cautionnement) deposited by proprietors and editors of papers with the government equally a guarantee of proficient behavior. Finally, a skillful interpretation of the law on clubs and political societies suppressed most this time all the republican societies. It was now their turn to be crushed like the socialists.

Coup d'état and end of the Second Republic [edit]

However, the president had only joined in Montalembert's weep of "Down with the Republicans!" in the promise of effecting a revision of the constitution without having recourse to a insurrection d'état. His concessions only increased the disrespect of the monarchists, while they had but accustomed Louis-Napoléon as president in opposition to the Republic and as a step in the direction of the monarchy. A conflict was now inevitable betwixt his personal policy and the majority of the Chamber, who were moreover divided into legitimists and Orléanists, in spite of the death of Louis-Philippe in August 1850.

Louis-Napoléon exploited their projects for a restoration of the monarchy, which he knew to be unpopular in the country, and which gave him the opportunity of furthering his own personal ambitions. From 8 August to 12 November 1850 he went about French republic stating the case for a revision of the constitution in speeches which he varied according to each place; he held reviews, at which cries of "Vive Napoléon!" showed that the army was with him; he superseded General Changarnier, on whose arms the parliament relied for the projected monarchical coup d'état; he replaced his Orléanist ministry building past obscure men devoted to his own cause, such as Morny, Fleury and Persigny, and gathered round him officers of the African army, broken men like General Saint-Arnaud; in fact he practically declared open up war.

His reply to the votes of censure passed by the Assembly, and their refusal to increment his ceremonious list was to hint at a vast communistic plot in society to scare the bourgeoisie, and to denounce the electoral law of 31 May 1850, in order to gain the support of the mass of the people. The Associates retaliated by throwing out the proposal for a partial reform of that commodity of the constitution which prohibited the re-election of the president and the re-establishment of universal suffrage (July). All promise of a peaceful consequence was at an end. When the questors called upon the Bedchamber to have posted upwards in all barracks the decree of six May 1848 concerning the correct of the Assembly to need the support of the troops if attacked, the Mountain, dreading a restoration of the monarchy, voted with the Bonapartists confronting the measure out, thus disarming the legislative ability.

Louis-Napoléon saw his opportunity, and organised the French insurrection of 1851. On the dark of 1/ii December 1851, the ceremony of his uncle Napoleon's coronation in 1804 and his victory at Austerlitz in 1805, he dissolved the Sleeping room, re-established universal suffrage, had all the political party leaders arrested, and summoned a new associates to prolong his term of office for 10 years. The deputies who had met under Berryer at the Mairie of the 10th arrondissement to defend the constitution and proclaim the degradation of Louis Napoleon were scattered by the troops at Mazas and Mont Valérien. The resistance organized by the republicans within Paris under Victor Hugo was before long subdued by the intoxicated soldiers. The more serious resistance in the départements was crushed by declaring a country of siege and by the "mixed commissions." The plebiscite of twenty December, ratified by a huge majority the insurrection d'état in favour of the prince-president, who solitary reaped the do good of the excesses of the Republicans and the reactionary passions of the monarchists.[vi]

References [edit]

- ^ "Les couleurs du drapeau de 1848". Revue d'Histoire du Xixe Siècle - 1848. 28 (139): 237–238. 1931.

- ^ a b Mona Ozouf, "Liberté, égalité, fraternité", in Lieux de Mémoire (dir. Pierre Nora), tome Iii, Quarto Gallimard, 1997, pp. 4353–4389 (in French) (abridged translation, Realms of Retentivity, Columbia University Printing, 1996–1998 (in English))

- ^ Arnaud Coutant, 1848, Quand la République combattait la Démocratie, Mare et Martin, 2009

- ^ Maurice Agulhon, The Republican Experiment, 1848–1852 (1983)

- ^ Alec Vidler (1990). The Penguin History of the Church: The Church building in an Age of Revolution. Penguin. p. 86. ISBN9780141941516.

- ^ Roger D. Toll (2002). Napoleon III and the Second Empire. Routledge. pp. 1834–36. ISBN9781134734689.

Sources [edit]

- This article incorporates text from a publication at present in the public domain:Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "French republic: History". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 801–929.

Further reading [edit]

- Agulhon, Maurice. The Republican Experiment, 1848–1852 (The Cambridge History of Modernistic France) (1983) extract and text search

- Amann, Peter H. "Writings on the 2d French Commonwealth." Journal of Modern History 34.four (1962): 409-429.

- Furet, François. Revolutionary France 1770-1880 (1995), pp 385–437. survey of political history by leading scholar

- Guyver, Christopher, The Second French Democracy 1848-1852: A Political Reinterpretation, New York: Palgrave, 2016

- Price, Roger, ed. Revolution and reaction: 1848 and the Second French Republic (Taylor & Francis, 1975).

- Cost, Roger. The French Second Democracy: A Social History (Cornell Upwardly, 1972).

In French [edit]

- Sylvie Aprile, La Deuxième République et le 2nd Empire, Pygmalion, 2000

- Choisel, Francis, La Deuxième République et le 2nd Empire au jour le jour, chronologie érudite détaillée, Paris, CNRS Editions, 2015.

- Inès Murat, La Deuxième République, Paris: Fayard, 1987

- Philippe Vigier, La Seconde République, (series Que sais-je?) Paris: Presses Universitaires de French republic, 1967

Coordinates: 48°49′Due north 2°29′E / 48.817°N 2.483°E / 48.817; 2.483

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Second_Republic

0 Response to "When Did France Become a Republic Again"

Post a Comment